Précis

In Women’s Literature, my classmates and I read multiple texts that crossed and blurred genres, including Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee and Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons. Similar to my project, “Conscious Beasts: Poems,” I created a project in my chosen genre, this time blending poetry, prose, and visual images. My project developed in an unconventional way, as I ended up creating pieces that were fairly different from what I originally planned. I initially intended to write a creative essay, but I found myself generating poems and visual images. With this shift, my pieces more closely interact with Tender Buttons and Dictee now by mirroring their experimental and nonconforming forms.

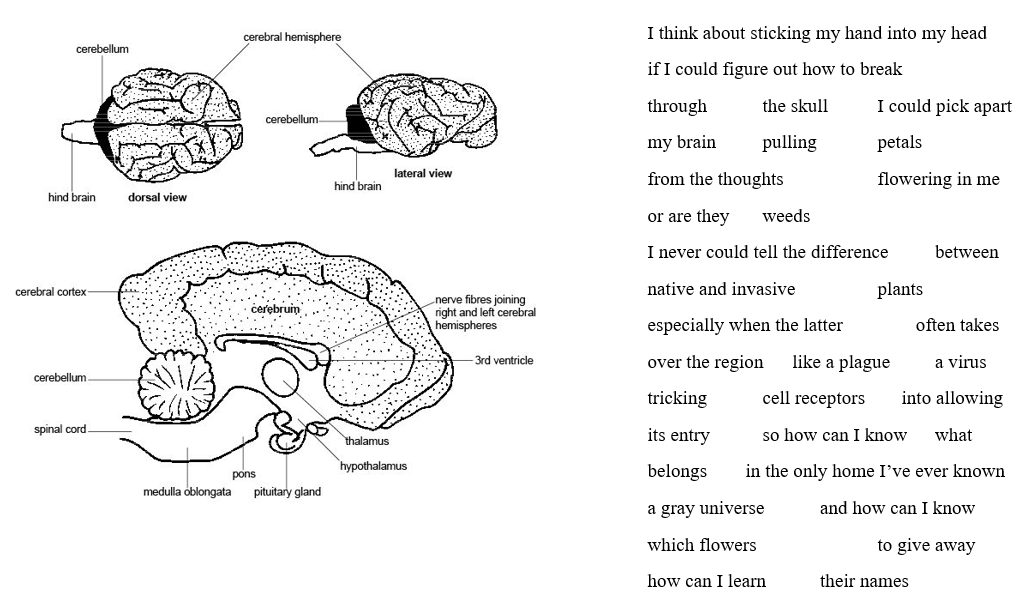

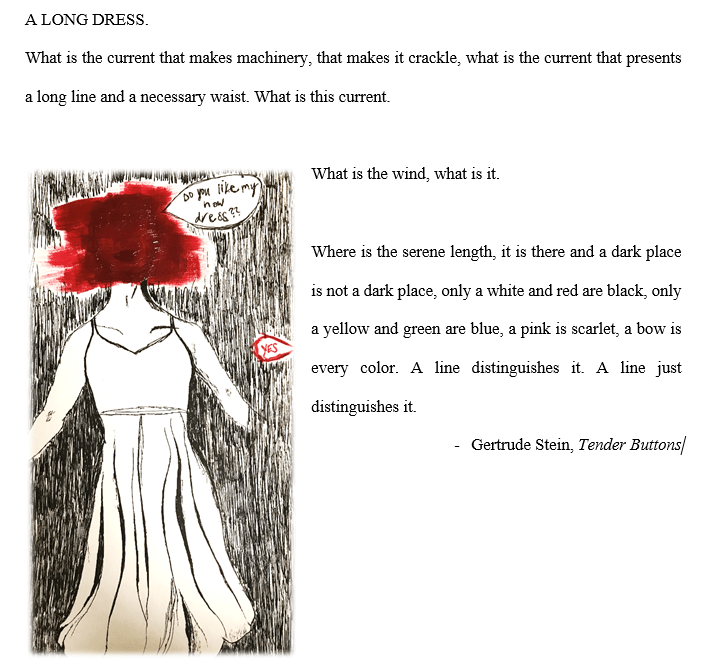

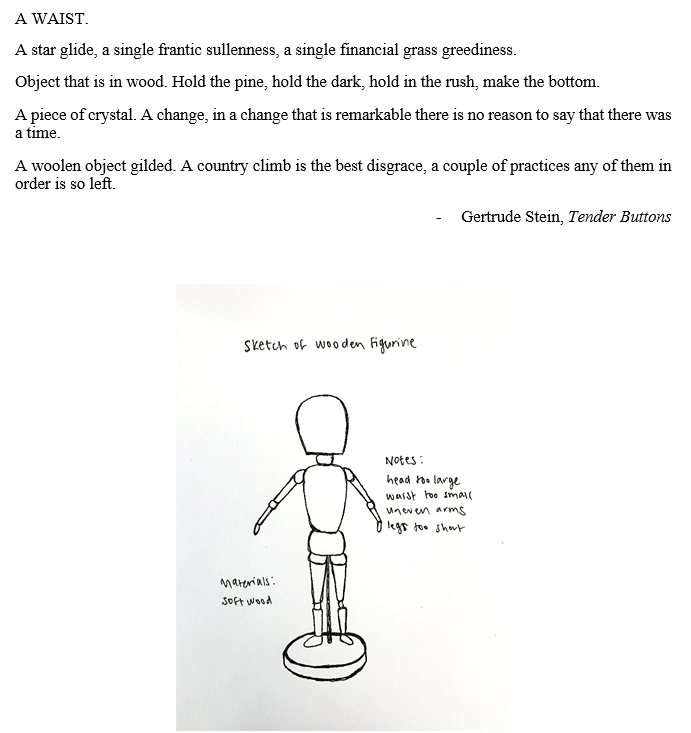

I engage with Tender Buttons directly by illustrating an ekphrastic response to excerpts from Stein’s writing, as demonstrated in the piece titled “Building the Perfect Figure,” which allows me to visually display the images and ideas that arise for me when reading Stein’s work. While I engaged with Dictee less directly, aside from a poem of mine—“Anatomy of the Brain”—that imitates one of Cha’s, I draw inspiration from the ways in which Cha portrays various forms of communication. Her book, Dictee, includes written and visual forms including numbered instruction lists, political documents, portraits, diagrams, and more. Since both Tender Buttons and Dictee are difficult texts to analyze, as the former uses surreal language and the latter uses multiple dialects, the genre project is helpful in engaging with the texts without the pressure of formatting, grammar, syntax, and other elements of the academic essay. Both texts intentionally challenge the conventions of scholarly writing and thus require an innovative response. Moreover, using mixed genres in my project allowed me to embody the styles utilized by Stein and Cha, giving me a deeper understanding of their literary choices.

Some of the forms and language I use differ from Stein’s and Cha’s work, as I decided to experiment in a more contemporary space and to stay true to my authentic writing style, but I heavily draw on themes from their work. While Stein mainly describes household objects, her surreal and figurative language implies that she is reimagining these mundane images. Moreover, she challenges the styles of prominent writers—including, but not limited to, Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald—and gender norms during her time. As a masculine-presenting woman with a female partner, Stein did not adhere to societal expectations for woman. Her portrayal of daily objects thus indicates that she is seeing the household in a new light due to her gender identity and sexual orientation. Stein’s work offers insight into the intersection between language and gender, a connection that I explore in my own work.

The relationship between gender and language is most evident in the pieces, “Constructs” and “bitch (noun),” which discuss how society assigns gender to language. “Constructs” is not necessarily a poem but also not an essay; rather, it is a vignette that centers on the idea of how both gender and language are culturally constructed. This vignette, along with “Signs,” are not in a specific form and are, instead, meant to mirror the motion of my thought process. These two vignettes function as reflections that frame the poetic and artistic pieces. As some pieces focus almost exclusively on language, while others focus mainly on gender, “Constructs” especially serves as a bridge between these concepts. Furthermore, form, or the lack thereof, is very purposeful in this project. An example is in “female body,” which examines female experiences with the body. I chose to write in the prose poem form and to exclude punctuation as a visual representation of the anxiety that I, as a female, have experienced when I am self-aware of my body in public spaces. The lack of capitalization also illustrates the experience of feeling small due to gendered power dynamics. This poem is not meant to be impressive in terms of language and sound, but, rather, to explore how form can contribute to the feelings expressed in a poem. Furthermore, form is used intentionally to represent the prominent themes—gender and language—in the project.

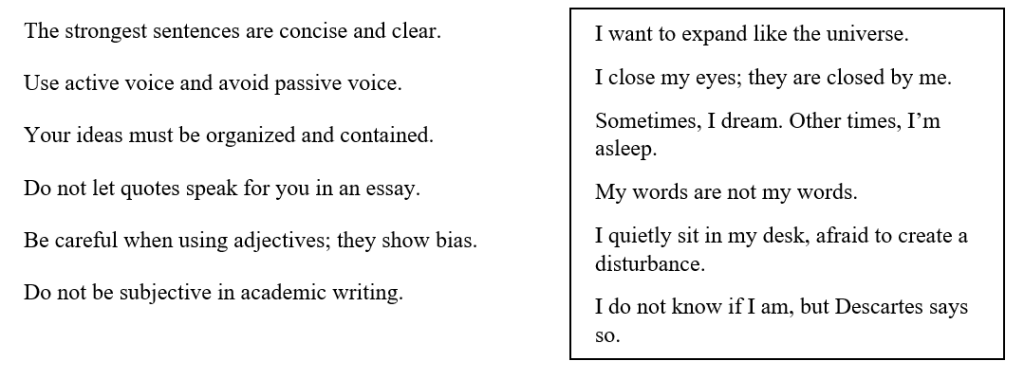

Work from “Hybrid Forms”

How to Write a Strong Academic Essay

Signs

In an English grammar class, the professor asked us to define language. Essentially, we all said that language is a means of communication. Oxford agrees, but specifies that the communication is written or spoken.

Frida Kahlo did not consider herself a Surrealist; she said, “I paint my own reality.”

I hate this cliché: a picture says a thousand words. However, I have heard voices while standing in art museums—Bosch’s voice sounded like screeching birds and Goya’s voice like blood. They are both dead, but I swear I heard them in El Prado.

What I like about visual art is that it transcends boundaries. Written and spoken language has a harder time moving across geographical and social lines. There are “correct” ways to write and speak, but if the purpose is to communicate and that purpose is fulfilled, then how can there be an incorrect way?

This is about language and it’s not.

“Do you like my dress?”

female body

i want to be looked at but only when i want to be looked at and most times i don’t want to be looked at but that doesn’t stop me from being looked at and no i’m not going to take it as a compliment because they are not looking at human me but at me who is tangible to them who is legs and warm and they tell me don’t dress like that then as if i were picking my clothes that morning and deciding oh this random stranger who i have no current knowledge of is probably going to want to look at me if i wear this skirt and god forbid my knees are visible because knees are very suggestive and shoulders are very suggestive and brief eye contact is very suggestive and smiling is very suggestive and my gender is very suggestive and

Building the Perfect Figure

Constructs

In Spanish, words are clearly labeled as masculine or feminine, using the determiners la (feminine) and el (masculine). English is a bit more implicit when it comes to assigning gender to language. Is the language itself inherently gendered, or have those who speak the language come to associate certain words with a certain gender? The latter option appears most logical to me. After all, a dress is only a “feminine” article of clothing because it has traditionally been a social norm for women to wear dresses. If you strip away the social norm, though, the dress is just a piece of fabric and nothing more.

bitch (noun)

/biCH/

1. the female of the dog or some other carnivorous mammals

2. informal + often offensive: a malicious, spiteful, or overbearing woman

3. informal: something that is extremely difficult, objectionable, or unpleasant

(Merriam-Webster)

I have been called it before

in school hallways and arguments

on the phone, the sound lingering

in the air like burnt

hair and sticking

to my clothes, my skin. The voiceless

palatal fricative starts at the back

of the tongue and gently taps

the hard palate, vocal chords

remaining still so that the phoneme

is soft and airy when it escapes

the mouth. Yet, the subtlety

does not subtract from how the word

smacks the eardrum, how the meaning leaves

its mark in a way that cannot be ignored.

Stop being so sensitive. I’m

just joking. I usually laugh

because maybe they’re right—

it’s just a word, but then

isn’t every word just a word?

Isn’t everything just everything?

A face is just a face, and a bullet

is just a bullet.

Anatomy of the Brain

after Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (pp. 74-75)